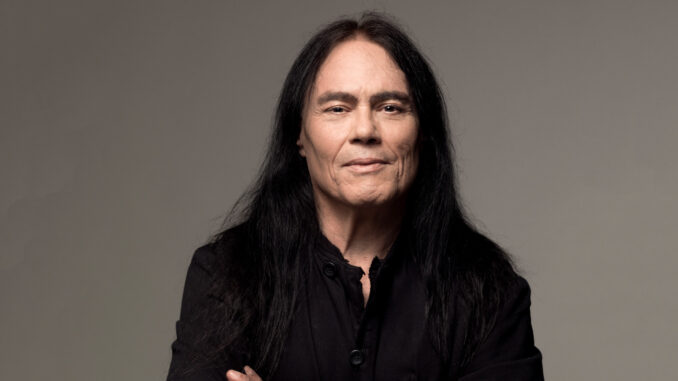

If he’d stopped playing after recording the iconic intro to Tarot Woman and the influential solo to A Light In The Black on the uber classic, Rainbow Rising, then Tony Carey’s stature in music would have been assured, even if he never recorded another note. Fortunately, he didn’t stop there. Over 40 years and 30 albums later Carey has just released his latest and most personal album to date. Mick Burgess called him up to talk about the stories behind his new album, his time in Rainbow and his plans for a series of new releases over the coming months.

Your new album, Lucky Us, has just been released. Are you pleased with the response you’ve received so far?

It’s only been out a short time but the reaction has been fantastic and it’s really exploding, even in America which is amazing. I’m very pleased with what people have been saying about it.

It’s only been out a short time but the reaction has been fantastic and it’s really exploding, even in America which is amazing. I’m very pleased with what people have been saying about it.

When did you start work on the album?

Some of the stories that I’m writing about go back to the 50s but I started working on the actual album about 5 years ago after I had my last cancer operation. I had a 10-year period where I had 6 operations for bladder cancer that had all sorts of complications and I went through a divorce and was down and out. I was then with Jurgen Blackmore in a band for a while, that was more of a moral support thing because he’s my buddy. I then met my now wife Marion, who you can see in the album booklet. I thought I was getting old, I’m 66 this year and had been wondering for a while whether I should do another record.

What made you decide to do one now?

Marion encouraged me to do one and the first song was Lucky Us. I’ve actually done another four albums since then but Lucky Us was the starting point. The only thing I’d never really written about was myself. People have been asking me to write a book but I hate all of these Rock ‘n’ Roll books about drugs, sex and throwing TV’s out of the window. I didn’t want to do that. I was sitting in the garden with Marion and she was asking me about my childhood and I thought it was time to tell that story. I wanted to take the coldness out of the world and make it a little warmer place which is all you can really do.

What’s the inspiration behind Lucky Us?

I basically started to think about the way we grew up and what we all had to go through. Lucky Us is about several things. Firstly, my Dad didn’t have to go to war as he was an agricultural worker and was exempt. He moved to Turlock, California on the Hawkeye Road, where I grew up. I had three brothers and we grew up oblivious to all of the problems that were going on in the likes of Alabama. Lucky Us is also our story. I first met my wife 30 years ago but we lost touch. Later on, we bumped into each other at Frankfurt airport and she remembered me and we picked up where we left off and ended up getting married. Lucky Us is also about winning the lottery of life. We don’t have to drink muddy water, we haven’t been bombed and we have a decent standard of living compared to many people on this planet. On a literal basis it’s our love story but in the overriding cosmic sense it means quit your bitching and look ahead as we’ve really got it good.

Hawkeye Road is a vivid telling of your childhood and carefree days of playing outside in the countryside. I think many people of a certain age can relate to those pre-internet days, spending all day playing out and only coming in when it was tea time?

I’ve been getting that a lot from people of our generation. We’d be out all day, no bicycle helmet, no helicopter parent, no iPad, nothing. We would play on Jungle Jim swings, you’d fall off them and get back up and go right back on them again. We’d be out all day and only come back when we were called back in for lunch. I had these ultra-supportive parents who were fabulous. That’s memories of my childhood.

Have you been back there since you left?

There is a saying that you can never go home again. You can’t go back again, there is no home to go back to. Turlock, California is not 7000 people anymore, it’s 80,000 people. Hawkeye Road is now east Hawkeye Avenue and has six lanes of traffic. If you do go home, there’s nobody there. They are all dead or have moved on. What’s happened has happened and you shouldn’t worry about going back to where you were. Keep looking ahead and don’t look back. That’s one of the themes of the Lucky Us album but I can still hear the choir in the church and I can still smell summer in the air and that’s the memory of Hawkeye Road.

It also tells of your Dad buying you a keyboard. Did you come for a musical family?

We didn’t have any money. I’d been fascinated by church organs. The town I lived in had the most churches for a little town of 6000 people. It had something like 85 churches or something. The sound of the church organ just got me and the second verse of Hawkeye Road said that I found out what I wanted and it was 1959 and I was 5 years old when I heard the church organ.

How did you feel when you got your first keyboard?

Money was tight and my Dad worked hard and my mother didn’t work as 50s women didn’t and there were three kids to feed. Somehow, he came up with $250 and that was a ton of money in the 1950s. It was a Lowrey organ and the cool guys on the other side of the tracks had Hammond organs but I could play 96 Tears, Gloria and House of the Rising Sun on it. My brother knew how to plug it through a tiny guitar amp and make it scream. I learned the first three Doors albums on that organ, note for note. I was totally self-taught. They didn’t lock the doors in those days so I used to go around to the church most days, the door was always open and I used to tinkle on the out of tune piano they had. Nobody told me that I couldn’t and my Dad got wind of that, the intuitive, compassionate man that he was. It was my 14th birthday and I wasn’t expecting anything, I think I was hoping for some comic books or something like that. A pick up truck went by my house and it had a white tarpaulin thing over it but I could see a musical instrument on it as he drove past but he turned around and he had my Lowrey organ on it. It was the biggest day of my life and I’ll never, ever forget it. I don’t have it any more but there’s a picture of it on the album. As soon as I turned into a real big shot Rock ‘n’ Roll star at 16, I got a Hammond.

Your parents must have been pretty supportive of your musical ambitions?

This is how cool my parents were. They gave us the living room and let us play and play and play, while they sat in a little add on my Dad built so they could sit and talk or listen to the radio. They never got that living room back. Playing felt like flying to me and nothing about that has changed. That was Hawkeye Road.

On an album full of strong, moving melodies The Wind is probably the most touching. What inspired you to write that song?

I’ve got four girls. The youngest is 20, the oldest is 46. I have people I love and people I care about. We all do. As you get a little older you realise that you have to be there for them no matter what comes. You give them the benefit of your life experience and your compassionate life support and unconditional love. We live in scary times where Donald Trump can threaten North Korea with fire and fury and I realised that I live 40km from Frankfurt which is one of the main financial capitals of Europe. I once read that there were 250 nuclear warheads aimed at Frankfurt. For the first time since the Cold War ended there’s all this talk about nuclear annihilation. If they fired those at Frankfurt there’d be an incredible light show but very little warning. I worked out it’d take three and a half minutes for the shock waves to get here where I live. I said to my wife, that if that happened, we’d take a garden chair down to the last cherry tree in the garden, we’d watch the light show and in three and a half minutes there’d be this big wind and everything would be gone. It is the compassionate obligation to take care of the ones you love but you can’t stop a hurricane, you can’t stop a flood but you can be there. So, this is I can’t stop the wind, I can’t hold the waters back again but I will love you and will be there to the end. That’s the story and it’s based on Donald Trump’s fire and fury speech. I call those type of songs chocolate covered arsenic pills so when you get inside of the story you go oh, OK.

A few years ago, you were diagnosed with cancer and Hallelujah (I’m Alive) tells your story of those times. When were you going through this?

In 2009 I got diagnosed. Back then someone had suggested I do a band with my buddy Jurgen Blackmore called Over The Rainbow. I don’t do covers but I figured it’d be like the real Rainbow where we’d just let loose and play like we did in the ’70s but it turned into Joe Lyn Turner’s Jukebox and he wanted to do 4 minute songs which in fairness is what his vision of the whole thing was. He was an 80s guy and I was more a 60s guy and was up for a jam. In the middle of that I was diagnosed with bladder cancer and they took out a lot of my organs, not my Hammond organ but they took everything else.

What made you suspect that something was wrong?

I noticed a drop of blood in a place a drop of blood shouldn’t be and went right to the doctor. Yet again I thought Lucky Us, because here in Germany there’s socialised medicine so we are so lucky to have access to this healthcare that they just don’t have in America. Within a day and a half, I was in the hospital having an operation. A hospital is a good place to go to get sick. The cancer was OK but the antibiotic resistant super bacteria got me. In eight hours, I was cured of cancer but that’s when the infections started. I had sepsis four times and that has a mortality rate of 70%. The doctors told my youngest daughter that it might be a good time to say goodbye to your Dad. She said no way, you weren’t taking my Dad. I went under the knife and they opened me up and when I woke up, I only had one thought, Hallelujah I’m Alive. I was crying and she was crying and I wrote that song that very day. I was so proud of her and so grateful that the song just came out.

I had pretty much the same sort of cancer as Ronnie James Dio. I hadn’t heard from him in years but I always stayed in touch with Wendy. I asked her what happened. She thought his cancer was caused by life on the road, what he was eating and not getting enough sleep. It was the same with Jimmy Bain, he died on a cruise ship with undiagnosed lung cancer. They wouldn’t even give him health insurance in America. Jimmy was my brother in arms. We were the two Punk kids against the Rock stars. Ronnie was OK but Ritchie and Cozy were fairly full of themselves.

Johnny Boy tells the story of a soldier who didn’t return and the effect on his family. Is that written about a particular person or a song in general for those that go away and never come back?

It is about a person I know but once again during the 2016 campaign Trump managed to insult a patriotic Muslim family. There are as many Muslims in America as there are Jewish people and many more than there are Hindus. A lot of them are in the army because they are patriots and grew up in America. The bottom line of all religions is don’t be a dick and if you are, try to make it better. So, Trump insulted this Gold Star mother who lost her son in battle. The story of the song is about a Gold Star mother with tears in her eyes and there is one more brother left to sacrifice and he has gone missing and she fears that he will be her second Gold Star. I named the boy in the song Johnny after the American Civil war song. He’s missing in Afghanistan, his mother has already lost a son and has a Gold Star hanging from the window and she’s scared shitless that she’ll get a second one. So that’s what that song is about.

Is The Goodnight Song the advice you got from your parents that you have passed on to your own kids?

That’s about what my Dad told me when I was a kid. The first word that any kid learns that has power is the word “no” and the next word is “why?” My father would put us to bed and he’d chat to us and he’d tell us stuff about the universe and oceans and stuff like that. He would always end by saying he was turning off the light and that we mustn’t make him come back but he’d always say this, “just remember you can be anything that you want to be, if you reach for the moon, at least you’ll touch the sky”. In the last verse we get back to the central theme of the album in that “I will be there for you”. He basically was saying turn out the lights and I will still be here for you when you wake up in the morning.

Was that quite a cathartic experience for you making this album?

It’s impossible getting down everything that’s in your head. This one was particularly difficult because in the past I’ve produced Joe Cocker and John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, I’ve produced a lot of people and I’m very experienced with a guitar, drums and bass line-up type of thing which I can pull together reasonably easily. The hardest thing I’ve ever done is a piano album with just a little bit of orchestra where it just sounds like someone has stuck a mike in a room with a couple of string players. It can sound thin and I was looking for something much more expansive. I’ll never do a piano/orchestra album again unless someone else was doing it, it was so difficult. I mixed it 30 times and I’m still not happy with it. It was technically such a challenge to get the warmth that I was looking for. I actually like it but I’m a real perfectionist. If I’m going to do it without the expectation that anyone is ever going to hear it at least I’m going to do it as well as I can and I don’t care how long it takes. I was doing it in the expectation that I’m too old and nobody wants to hear it, I am a cancer survivor and I’m tired, I have grandkids, maybe I should go to Norway and go salmon fishing and take it easy but I’ve actually got more stuff to say. I was sitting in the garden with Marion and she was asking me about my childhood and I thought it was time to tell that story. I wanted to take the coldness out of the world and make it a little warmer place which is all you can really do.

You’ve had a career in the music business spanning over 45 years. How do you feel about that looking back on it?

When I was 18 I’d left High School and started a band and we got lucky and we got a record deal. They brought us out to LA and Ritchie Blackmore heard me play. He wanted somebody to join him and he’d heard me through about eight concrete walls. I wasn’t really a Rock guy but I liked good Rock. In 1981 I got lucky again as Geffen Records was starting and I’d been in Germany for three years and was recording all the time and just learning by doing things. I’d never been a singer, never been a lyricist and was goofing around inventing Techno after listening to Kraftwerk and Can and I was experimenting with drum machines making all different types of music and ended up getting Planet P Project signed to a huge American record label. I featured on MTV and at that time there were about 12 MTV videos in existence and I had two of them. I was in this one bedroomed apartment in Frankfurt going to the studio every day and all this action was going on in America.

Did you feel like you’d started to reap the rewards of your hard work at that point?

My manager made a deal with me and then he made a deal with the record company so instead of me making a deal with Geffen Records he did and the label paid him and he was supposed to pay me and he didn’t pay me a penny. So, my first seven singles charted in America and I had a No.1 on Rock Radio and I never saw a penny. I knew that the records were Gold and Platinum as I’d written the songs and got publishing statements but I’d signed the publishing rights away and didn’t get any royalties and this went on for a long time as I was young and dumb, only 25 years old at the time. I sued this guy twice and he went insolvent twice so by this stage I was really disillusioned by the record business. Fast forward 10 years to 1994 and East West Records was now Universal like everyone else. They sent me to New York City to Quad Studios in Times Square. They paid $450,000 for an album I did called Cold War Kids with Marc Cohen’s production team. I had an ironclad promise that they’d release it world-wide so I could capitalise on the success I’d had in the ’80s. It ended up being released in Norway, Switzerland and Germany and no English-speaking countries. When they wouldn’t release it or promote it, I walked into the record company with a cheque and told them that I was gone and at that point I left the music business in 1994. What I didn’t leave was music. I hate the music business. There’s so many sharks out there that’ll eat you up, puke you out and eat you up again. That’d be OK if there was any element of humanity in it but there’s not. So, I’ve made an album a year since 1994 and I have about 43 unreleased officially albums done where I own the maters and the publishing. I don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to use any of my music.

Was joining an established band like Rainbow a daunting move for you?

Are you kidding me? I kicked Ritchie’s ass and made him a better player. I was 20 when I joined Rainbow and I wouldn’t let him get away with anything. Cozy Powell, the cockiest man I ever met, called me cocky. He said that Ritchie fired me because I got too cocky. I didn’t get fired because I left. I left three times and he rehired me three times after he tried literally everybody else in the world. Everybody seemed to be scared of him, sure he could shred but I could shred too. I wasn’t afraid of him. He just didn’t like him. He really hated me and his people skills aren’t what they could be but he could play and I never saw a showman like Ritchie Blackmore, he was just magic, just an amazing showman. He taught me a lot.

Does it surprise you that over 40 years after you were in Rainbow that people still talk about it?

It does. I don’t really take it as a compliment but I respect the fact that people mean it as a compliment. We made Rising in a week. We had Martin Birch keeping the peace. I must have played a total of 3 or 4 hours on that record and we had very little rehearsal. Ritchie told me that he needed to start the record off with something interesting. He said that we should get the new kid to do something as he was going to the pub. I asked Martin Birch what he meant and he said he wanted a keyboard intro so I said OK. We did two takes over an hour. Ritchie came back in and listened to it and said it was interesting and he’d take it. I did another one for Stargazer that never made the album although it might be on the deluxe version now. Then there was A Light In The Black. He had the grace not to be there and I wasn’t there when he played. I played it in a high shredding Mini Moog sort of way. If Ritchie liked something, he’d say it was OK. Some might be insulted by that but that’s just how he said he liked something and he said my solo was OK.

Did you put the eastern theme into Stargazer?

I certainly did not. Ritchie was inspired by Kashmir and wanted something similar. He sang what he wanted to me. It was all Ritchie’s composition but I did teach him to play the keyboard/guitar theme in A Light In The Black.

The keyboards in Tarot Woman and A Light In The Black are two key parts to those songs. Do you feel that you should have had a song writing credit for those?

Have you heard On Stage? What do you think that 45-minute keyboard solo is worth? This was all about the Rock and Roll school of Fuck You economics? Of course, I should have had a song writing credit. They didn’t even credit me with my playing on Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll until last year. Officially David Stone played on the whole album but I know he played one song, Gates Of Babylon and most of the rest was me. They wrote me out of it but I definitely did Rainbow Eyes and Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll and can hear the low growl of my Hammond throughout. I left in the middle of making that album.

The interplay between the musicians was incredible live on stage, was that mainly improvised?

All of it was. We did not rehearse. It was free and improvisational as Jazz. We didn’t have to love each other to do that. The tension was always there. In fact he fired me on stage in Bristol because I played something, he didn’t like and he told me to go. I went back to the hotel and was ready to leave and he said that I couldn’t just leave but he just fired me and then wanted me back straight away.

Why did you end up leaving?

I ran away on December 7th and didn’t tell him I was going. I got a taxi to the airport in Paris. I thought I was going to die. It got violent and I don’t do violence. I called my old man using a pay phone and told him I wasn’t going to make it. He told me to get to Charles De Gaulle airport and there’d be a ticket waiting for me. I told the road manager Colin Hart that the line had been drawn and I was gone. He was a lovely guy and he booked me a taxi to take me to the airport. I haven’t seen or heard from Ritchie again since then. I was in the band from early ’75 to late ’77.

Over the years you’ve covered many styles from the Neoclassical style of Rainbow, to the more futuristic electronic Planet P Project and the melodic Rock approach of the likes of Some Tough City and Blue Highway. Does that ability to vary your styles keep the creative process fresh and interesting for you?

I don’t think that at all. I think it cost me a career. I once read a great review of AC/DC’s album that they did after Back In Black and it said, it sounds just like an AC/DC album and the review said, so what’s the problem with that? That is actually how it should sound. You could never pin me down and put me in the draw and that has cost me. If I’d stuck to a genre, for instance, Hard Rock, it could have been very different. I could have left Rainbow and joined any Rock band in the world. That gave me major Rock credibility to play with Ritchie but I wanted to do something else. A Fine Fine day was Number One in American Rock Radio in 1984 and I could have moved back to LA and been like Bryan Adams and had a good career but I didn’t want that. It helps me with my music but I make my music for myself but I’m gratified when people like it. The diversity has caused me more problems than it has solved. I’m a self-described beat poet and I go where the wind blows whatever I feel like doing at the time, that’s what I do and that is a wonderful freedom to have and I’ll end this by saying “Lucky Me”

You’re an American but live in Germany. Why did you move there?

I’ve lived here for 41 years. I moved to Germany in 1978 as I felt I could be in Oslo or Prague or Madrid within two hours. I liked the central base that it gives me. I’ve had to learn the language of course but I like being here.

What are your touring plans? Do you hope to play shows across Europe and the UK too?

I’d love to come to the UK, I’ve never played the UK solo and haven’t actually played in the UK since the ’70s. With this show, all I need is a piano, I don’t need a band or anything so maybe I’ll finally make it over. At the moment I’m doing a tour called Songs and Stories. I’ll be speaking German to German audiences. I was asked what genre it was. I’ve done Hard Rock when I was a kid and in two months I’ll be starting my Frank Sinatra tribute album so I can show Mr Buble how it’s done so I said how about Americana with no fiddles. My album is just piano and orchestra but it’s American because of the lyrics, which are absolutely American beat poet, Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac type lyrics. I’m finding myself explaining to people in German what I’m about to do. I feel like a car salesman. When I play to an English-speaking audience, I won’t have to explain what the songs are about.

Do you get asked to take part in projects or play in other artist’s records much?

No more than 2 or 3 times a week. I’m never really tempted. That’s a young man’s game and I just about bluffed my way through Lucky Us after hurting my thumb. You have guys like Jordan Rudess who’d just blow me out of the water. I’m an old man so you can leave me out of all that.

Looking to the future, you have Lucky Us out now and some live shows lined up. Do you have any time for any other projects or production work or is that going to be family time for you?

I’m really grateful that I’m physically in a good place and I’m happy to be able to go out and play. From September until January I’m going to be releasing 12 records. These aren’t some bootlegs from 1976 from a club somewhere or other that are worth some money to a collector, they are real records. I just never felt the need to put them out before. I don’t do this to make money and hate every part about being famous but I do like to make music. I’m releasing a boxed set of the Planet P Project with five unreleased albums, I’m releasing a Christmas album, two albums of standards reflecting my roots of Sam Cooke, Wilson Pickett and Simon and Garfunkel. I’m about to do a Sinatra album with a Ronnie Scott All Stars and an orchestra so it’s all on my bucket list and so I want to get all that done before the bucket tips over.

Lucky Us by Tony Carey is out now.

See tonycarey.com for information on tour dates and new releases.

![RAINBOW - Rising [Deluxe Reissue]](https://www.metalexpressradio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/RAINBOW-Rising-Deluxe-Reissue-326x326.jpg)

The anti Trump stuff turned me off. I think he should do a bit of reading and realise that things under Obama weren’t so crash hot.

Trump is a piece of shit. Have a great day

This guy isn’t all there. He was never fired from rainbow. 30 sec.later: “Ritchie fired me on stage in Bristol.”. He doesn’t know that he’s not telling the truth. He thinks he never lies.

True. He once told me: “At least I never lie – my memory’s too shot to keep track if I do.”.

The biggest lie of all lies.